Breaking down the Revised Alice/Mayo test for 35 U.S.C. 101

Recently, USPTO (United States Patent & Trademark Office) proposed a revised set of guidance to conduct subject matter eligibility test (35 U.S.C 101) for patentable inventions, which is popularly known as the Alice/Mayo test and sought public suggestions for the same.

These revised set of procedures put forward the USPTO’s interpretation of 35 U.S.C. 101 by consolidating several judgments given by the Supreme Court and the Federal Circuit in several patent cases (most importantly in the Alice V. CLS Bank International & Mayo V. Prometheus Laboratories) pertaining to subject matter eligibility and judicial exceptions.

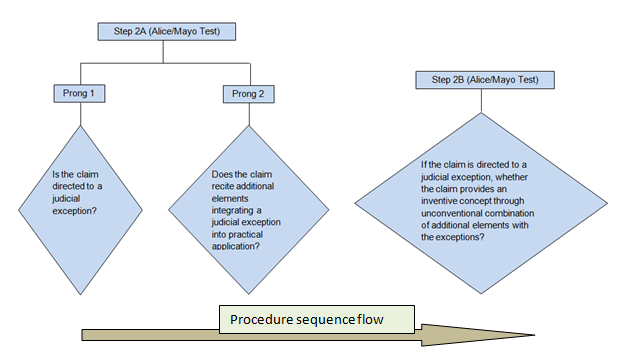

The Revised Alice/Mayo test overcomes previous shortcomings in understanding Section 101. Looking at the structure of the updated Alice/Mayo test and comparing it with the earlier existing model, the recent revisions have ushered in further simplification of the test into two sub-sections Step 2A and Step 2B, wherein Step 2A is similar to the Step 2 (2A & 2B) of the previous model.

This breaking down of Step 2A, into two prongs, and Step 2B helps in double-checking applications as in the Step 2A the examiner may consider an additional element was insignificant to overcome eligibility objection yet at Step 2B he has to reevaluate to see if the element or combination is unconventional in order to meet the requirement.

In Step 2A more importance is given to assess if a claim, in light with the whole invention, is “reciting” a judicial exception or is “directed to” one, while in Step 2B the combination of additional element with a judicial exception in an unconventional manner forms the basis of assessment.

The claim set is considered to be “reciting” a judicial exception/abstract theory if it makes use of the principle/science behind an abstract theory or similar concepts in the claim structure to achieve a result, however, the entire claim is not completely focused on that and talks only about the practical applicability of that abstract theory.

This is patentable under US law. However, a claim is “directed to” a judicial exception/abstract theory if the entire claim structure is built in such a way that monopolizes the judicial exception thereby restricting others from using the basic tools of scientific and technological work. To safeguard people’s interests, a claim “directed to” a judicial exception/abstract theory is not patent eligible.

Further, the “Abstract Theory” has also been comprehensively listed on the basis of judgments in previous patent cases, in line with the patent code in USPTO. This helps Examiner to ascertain with clarity whether an invention is an abstract idea or judicial exception.

In Prong 1 of Step 2A, the revised grouping of abstract idea includes the following: mathematical concept; certain methods of organizing human activity; and mental processes. Anything else may not be considered as an abstract idea.

However, under certain circumstances the USPTO employee may conclude that the subject matter though not belonging to the above groups may still be treated as an abstract idea and under such circumstances, the employee/Examiner should bring such application to the Technology Center Director (TCD) who may approve along with justification. This may be considered as a “tentative abstract idea” exception.

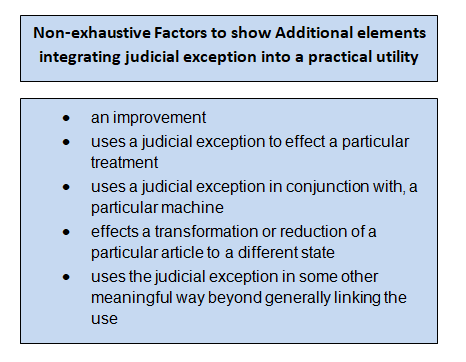

Further in Prong 2 of Step 2A, an additional element is considered to be integrating a judicial exception into a practical application if it reflects an improvement in functioning; applies or uses a judicial exception to effect a particular treatment; uses a judicial exception in conjunction with, a particular machine; effects a transformation or reduction of a particular article to a different state; or uses the judicial exception in some other meaningful way beyond generally linking the use such that it is more than a drafting effort to monopolize the exceptions. The mentioned list is non-exhaustive.

In Step 2B, further analysis is done to check whether the additional element(s), irrespective of its significance, present in the claim and their combination is unconventional and provide an inventive concept. If so, then this is considered to be patent-eligible because it adds significantly more than the recited judicial exception.

Thus, even if the invention fails at Step 2A it can still be patent-eligible provided that the combination of the additional element(s) with the judicial exceptions is an unconventional and inventive approach.

Looking at the overall picture, this revised Alice/Mayo test integrates previous judgments in patent cases along with the USPTO’s interpretation of patent law to devise a standard mechanism with fewer loopholes, improved transparency and credibility thereby clearing the ambiguity surrounding the 35 U.S.C. 101.

Resources:

1.2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/01/07/2018-28282/2019-revised-patent-subject-matter-eligibility-guidance

2.USPTO.gov

https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/101_step1_refresher.pdf

3.U.S.C. Title 35 – Patents

4.Alice V. CLS Bank International, Supremecourt.gov

https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/13pdf/13-298_7lh8.pdf

5.Mayo V. Prometheus Laboratories

https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/11pdf/10-1150.pdf

6.Analyzing the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance